As a deadline nears for a deal on Iran’s nuclear program, the talk centers around centrifuges, enriched uranium, and heavy-water reactors.

To understand what they are and why they matter, start with a look inside an atomic bomb. Stray bits of atom called neutrons collide with uranium or plutonium in the bomb's core, splitting the atoms apart and releasing enormous amounts of energy.

But not just any uranium will do.

The radioactive element comes in two main forms, or isotopes: U235 and U238. Only U235 will split. But this isotope makes up less than one percent of the uranium mined from the ground.

So the U235 has to be purified, or enriched. That is where the centrifuges come in.

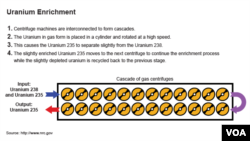

First, uranium is turned into a gas. That gas is fed into a centrifuge, a machine that spins at extremely high speed, separating the heavier U238 from lighter U235.

But they only separate a little. So the slightly enriched U235 goes into another centrifuge to separate a little more. Then another, and another. How many times depends on what it is for.

“If you enrich it to around three or four percent in the isotope uranium 235, you can use that to provide fuel for a nuclear power reactor,” said former nuclear negotiator Robert Einhorn at the Brookings Institution. “But if you enrich it to about 90 percent, then you can use it to build a nuclear bomb.”

Plutonium

Iran has also built a nuclear reactor that can run on natural, instead of enriched, uranium.

Experts worry because this kind of plant can turn uranium into the other bomb material, plutonium.

Plutonium forms when a neutron strikes U238, the isotope that makes up most natural uranium. Unlike U235, which splits when a neutron hits it, U238 absorbs the neutron and turns into plutonium.

When fed with natural uranium, the type of facility Iran has built, called a heavy-water reactor, can produce substantial amounts of plutonium.

It would not be the first time. “This is the kind of reactor that a number of other countries that are now nuclear-armed used to begin their nuclear weapons program,” Einhorn said.

But the heavy-water reactor can also produce radioactive chemicals used to treat cancer. With a few changes, it can still make those chemicals, but produce much less plutonium.

Even if Iran did produce plutonium in this reactor, it would still have to extract the bomb material from the reactor fuel. That requires a “reprocessing” facility, which experts do not believe Iran has built.

Negotiations

But using the uranium it has on hand, U.S. negotiators say Iran could produce enough material for a bomb in two to three months. The United States and others aim to push that time frame back to at least a year, in order to give the world time to react.

Some of the main issues on the table are reducing the size of Iran’s stockpile of partially enriched uranium and limiting the number of centrifuges.

The design of the centrifuges is also important, according to Barry Blechman, co-founder of the Stimson Center, a Washington research institute.

“You want to make sure they do not develop more advanced centrifuges, because the ones they have working now are kind-of the Model T version and it is very slow,” Blechman said.

Faster centrifuges would mean less time to a bomb. And more for the world to worry about.